How to handle your PhD: Part the second

Welcome back to part two of this blog+YouTube video double-whammy. If you haven't read and watched Part One, make sure you go back and do so. And don't forget to watch part two of the video!

And without further ado, let's continue the information dump on PhD-ing!

Science communication and outreach

Communicating your science is a really important skill to learn. Both David and I recommend getting involved in science communication (scicomm for short). The skills you pick up communicating your science to a general audience will also help you communicate your science to other researchers. We also need to be able to explain to the public and funding agencies what we do, why we do it, why it’s important and most importantly why they should be excited about it.

Some PhD students want to do science communication and outreach, but their supervisors may dismiss this as a waste of their time. In this situation, you may want to have a discussion with your supervisor about the benefits of scicomm, and also to point out that you want to be a scientist who communicates science, not necessarily the next Neil DeGrasse Tyson or Brian Cox (who largely prioritise entertaining communication over their scientist role), although there’s nothing wrong with aiming to be the next Face of Science!

Some examples you could bring up include:

- Scicomm improves communication skills for conferences and grant applications

- It builds your profile as a researcher

- Helps build your research group’s profile and publicises your research

- Some scicomm opportunities may include a monetary reward (David won $1000 through a science communication competition early on in his PhD!)

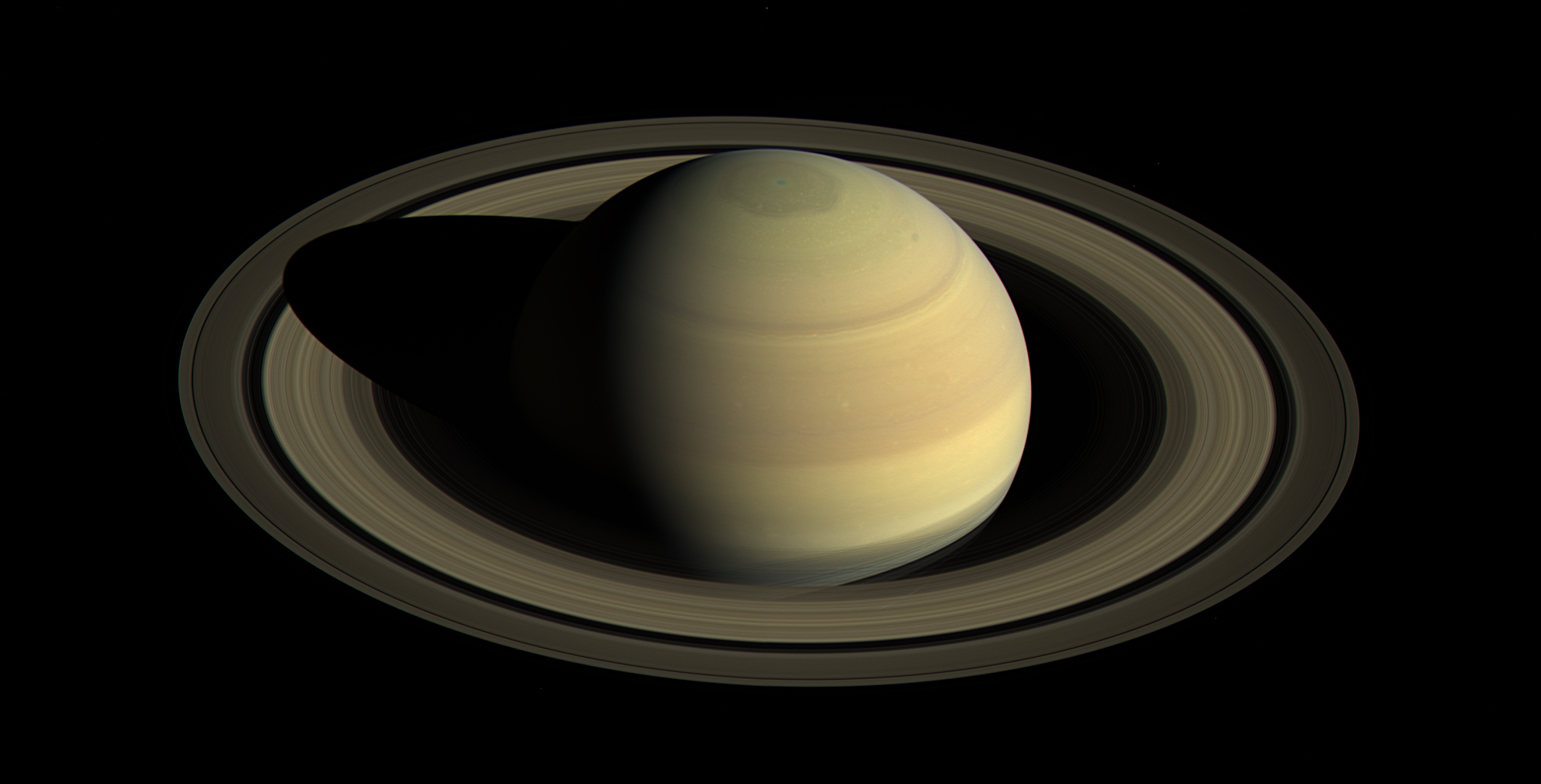

Some words of caution though - if you find your scicomm time is cutting into your research time, you may need to evaluate how effectively you are spending your time. If you are enjoying the scicomm way more than the research itself, consider looking into the graduate programs that specialise in scicomm. Also, it’s a good idea to include scicomm experience in your CV, however make sure you are selective about the activities you choose. Adding every single thing you’ve done can look like excessive CV padding. Pick the particularly significant events you’ve been involved with. In David’s case, this may be the times he’s won prizes. In my case, I highlight things like my involvement in the Cassini Mission grand finale as opposed to every podcast I’ve done.

Here's a gratuitous picture of Saturn from the Cassini mission. Science!

Those who can, do. Those who need money while doing it, teach.

Like scicomm, teaching also helps build communication skills as well as leadership skills. This is also a good way to attract new students to you research group. If you plan to stay in academia, the majority of academic roles will involve teaching in some capacity, whether it is teaching lecture courses or supervising students. Building teaching experience as a student is a good idea as this is likely to be one of the only times in your career you will have ‘spare time’ before it gets eaten up by writing grant applications, supervising students and dealing with a growing mountain of emails. And, as a student, teaching a class can be a welcome change from your usual desk or workbench!

Some jobs also require you to have some teaching experience and write what is known as a teaching statement, which will describe your teaching style and how it helps students learn. For this reason, it is a good idea to request student assessments of your teaching if your university offers this.

If you do want to pursue a research career, do consider trying to co-supervise an undergraduate or masters research student. Often, nobody will teach you how to be a good supervisor, but by working together with your own supervisor to mentor a younger student you can start to develop the skills you need.

There are some teaching qualifications you can obtain for university teaching. Individual universities often have courses you can take (they are frequently listed as ‘professional development’ courses and they are usually open to PhD students).

As with scicomm, sometimes you may find that teaching overwhelms your research. If this is the case, it may be a good time to re-evaulate your work load together with your supervisor. At the end of the day, its your research that gets you your PhD, not teaching.

When it starts go wrong - how to deal with problems

The kinds of problems that can impair the progress of your PhD are many and varied and there’s no way we can cover each one. They can range from your supervisor leaving, to being unable to access certain resources, to personal problems both inside and outside the institution. The key thing to know is what options and resources are available to you to deal with any problems that arise.

Your institution will often have all sorts of support structures for their staff and students: Counsellors, financial aid, a diversity and equity committee and many other services. It’s good to learn about these when you start your PhD, and certainly look for them if a problem does come up that you can’t solve yourself.

Your supervisor will often be the first person you can go to for help with a wide range of problems - this is why it’s important to have a good relationship with your supervisor. In general, you can help your supervisor to help you. Supervisors are often very busy people and are relying on you to be somewhat independent. You can make things more efficient by preparing as much as you can. If you are going to have a big meeting with them, put together an agenda. If you’re coming to them with a problem, try and have as much of the information they will need as you can already to hand.

Sometimes you can find yourself in a situation where the problem has been created by some kind of conflict with your supervisor. This may be due to something like not agreeing on whether or not a paper is ready for submission, but other issues can and do arise. This is why I recommend (and many universities require) having a panel of supervisors who can help mediate in these kind of situations. Another possibility is developing a relationship with a mentor who can step in to mediate if a disagreement occurs.

Choosing a mentor can be a bit tricky, but ideally you should look for

- Someone in a similar field, but outside your immediate field and supervisory panel who can provide some perspective on your progress

- Someone who has a career trajectory you would like to emulate

- Someone who may be able to provide a reference for you, whose name will be familiar to hiring panel

- Someone who can advocate if there is a disagreement with your supervisors

During David’s PhD, there was a compulsory mentor scheme implemented for PhD students, where they were required to meet at least once every six months with a mentor outside of our immediate research team. He was offered a choice of mentors and picked someone who he thought would provide a very different opinion to that of my supervisors. This has helped him immensely and it has been very good to have someone who has provided a contrasting voice to his supervisors.

One very common problem for PhD students is managing stress. It’s very common for stress and imposter syndrome to spill over into bigger problems like anxiety and depression. You may be surprised to find out that others around you may struggle with their mental health at times too (not necessarily limited to anxiety and depression). The important thing is that if you are feeling overwhelmed that you ask for help: all universities have counselling facilities, general practitioners and you can also access help outside the university through community programs. There are more and more online resources too. Organisations like Livin and Black Dog Institute (which has a host of excellent resources related to bipolar disorder in particular) are good places to start. Your friends can also be a port of call - in summary, don’t be afraid to reach out if you’re having a tough time!

Dealing with the inevitable: failure.

Failures do happen, and will happen to everybody at some point. At some point you are going to have to deal with a conference talk or a paper being rejected, not getting a grant you needed, or, in rare cases, rejection of your thesis. For smaller failures, like rejection of a paper, it’s important to remember that these things happen to everybody, it does not reflect negatively on you as a researcher, and to move on to the next journal, grant, or conference. For bigger stuff, like a major grant, or even your PhD, take time to mourn, then move on. Give yourself 24 hours to feel sad about the situation, maybe even take the rest of the day off and eat ice cream for dinner, but after 24 hours, it’s time to move on, sit back down, and work out the next step, work out how you are going to fix the problem.

One common place people being to feel “failure” is around receiving reviewer comments on their first paper. You will probably go through the five stages of grief: a mix of emotions, along with some anxiety or fear. This is quite normal - even experienced researchers don’t always enjoy reading feedback from a particularly harsh reviewer. Learning how to deal with the feelings you might experience about a reviewer response is part of the research process. I’ll be writing a blog in the near future with my tips and advice on the peer review process!

Doing what you came here to do: writing your thesis

The most important thing you can do when it comes to your thesis is start. I don’t think it’s ever too early to open a document, and start writing down bullet points about what you are doing. One other good reason for doing this is so you don’t forget all of the things you have done for your thesis. I also think it’s a good thing to keep everything you write. Even if you think it’s trash, hold onto it in a Google doc - you may find pieces that can be used and rewritten at a later date.

The most important thing is to actually start writing, even if what you write isn’t that good. Your supervisors will help you edit and refine your thesis and papers, and will provide feedback on your writing to help you improve.

You should also schedule some semi-regular time for writing, which is often a skill that gets de-prioritized in a science undergraduate degree and is hence a skill you will likely have to work harder at developing. Starting a blog (or taking to a microblogging platform like Twitter) can actually help improve your scientific writing skills. Another way to improve your writing is to read more scientific papers and theses in your field. This will help you ‘hear’ the kind of voice you need to be writing in for publications and your thesis.

When it comes to writing, like many aspects of research, you will find that ‘perfect’ is often the enemy of ‘good’ or even ‘finished’. You can spend so long making things just so that you may never actually finish the thing you started. At the end of the day, your PhD thesis has to be finished in order to be submitted, and that doesn’t mean it will be perfect. Perfectionism is a good trait when handled correctly, but it can lead to problems including, in some cases, anxiety and depression. This podcast from the ABC is a great discussion of how to work with perfectionism. If you do find this getting in the way of your work (which has happened to me), you could even work through this resource together with your supervisor.

Bonus round: Twitter

This info didn’t end up in the video, but both David and I could talk for months about Twitter. I’ve been using Twitter for almost ten years now, and I’m a certified Twitter addict (I have to turn off notifications or else I spend all day replying to people and scrolling endlessly). David was more reluctant, but looking back wishes he’d started using it earlier.

One really great reason to get on Twitter is related to networking. More and more scientists are getting involved in Twitter, and it’s a fantastic way to communicate with scientists during, before and after conferences in particular. In fact, David and I met briefly at a conference in 2016, followed each other on Twitter, and David has been annoying me ever since (his words, not mine)!

My big recommendation if you do get a Twitter account is to be yourself. Personally, I mostly avoid making political statements and for students, I would recommend this approach. However, getting involved in politics seems to work very well for people like Katie Mack and Twitter user @skullsinthestars. While David and I share science, we also share some details about our lives both related to (and not related to) research as well as the odd cute animal. One thing I like to try and achieve with Twitter is to communicate some of the science ideas I find interesting as well as showing that I have a life outside of astronomy and work.

Your can follow Fiona at @FiPanther and David at @DRG_physics. Both Twitter feeds are full of cool science, comments on the life of a researcher, and the occasional cute animal.

Overall, there can be a lot to consider when you decide to pursue a PhD, but both David and I would agree that it has been mostly a positive experience. While not every minute will be filled with fun, everything you encounter during your PhD can have a positive outcome. Even the hard bits can be viewed as a learning experience and a way to build the resilience you will need for a successful research career.

Wishing you luck, free food and kind, empathetic reviewers,

Fiona and David